by Comte de Lautréamont

translated by Samuel Lees

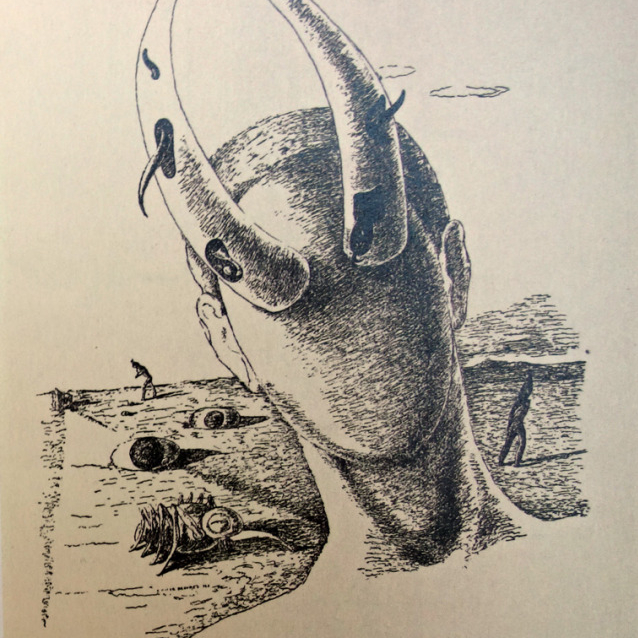

Before me I saw an object standing on a mound. I could not see its head clearly and yet I could tell that it was an unusual shape, without, nevertheless, being able to make out the exact proportions of its contours. I did not dare to approach this static pillar. Even with the ambulatory legs of over three thousand crabs at my disposal (not to mention those used for the purposes of prehension and mastication), I still would have remained where I stood, if an event, trivial in itself, had not taken a heavy toll on my curiosity, which was bursting at the seams.

A beetle, rolling, along the ground, with its mandibles and antennae, a ball whose principle elements were composed of excremental matter, was advancing at a brisk pace towards the aforesaid mound, making every effort to display its desire to proceed in that direction. This articulated creature was as big as a cow. Those who doubt what I say, let them come to me and I will satisfy even the most sceptical with the testimonies of reliable witnesses.

I followed it from afar, ostensibly intrigued. What did it intend to do with this huge black ball? O reader, who never ceases to boast of your perspicacity (and not without reason), would you be able to enlighten me? But I would not wish to put so severe a tax on your well-known passion for riddles. Suffice you to know that the mildest punishment I can inflict upon you is to tell you that this mystery will not be revealed to you (it will be revealed to you) until later, at the end of your life, when you will enter into philosophical discussions with death at your bedside… and perhaps even at the end of this stanza.

The beetle arrived at the foot of the mound. I had been following in its tracks but was still a long way from the scene of the action. For like the skuas, those restless birds ― as if they were always starving ― that thrive in the seas that bathe the poles and only venture by accident into the temperate zones, I was apprehensive and proceeded with caution. But what was the corporeal substance towards which I was advancing? I knew that the Pelecanidae family comprised four distinct species: the booby, the pelican, the cormorant and the frigate-bird. They greyish form I was looking at was not a booby. The plastic block I beheld was not a frigate-bird. The crystallised flesh I observed was not a cormorant. I could see him now, the acephalous man deprived of an annular protruberance! I searched vaguely through the winding convolutions of my memory: in which desert or glacial land had I already observed that very long, broad, convex beak with a pronounced, unguiculate bridge and a hooked end; those straight serrated edges; the branches of the lower mandible separated until the end; the interval filled with membranous skin; that large, yellow, sacciform pouch, occupying the whole throat and capable of distending itself considerably; and those narrow, longitudinal, almost invisible nostrils carved into a basal groove!

Had this living creature, with its simple pulmonary respiration and its body covered in hair, been a bird from top to toe, and not just down to the shoulders, I would have had no trouble in recognising it: an easy thing to do, as you yourself will see. Only, this time, I will spare myself the bother. For the clarity of my demonstration, I would need one of these birds to be placed on my work desk, be it only a stuffed one. Alas, I do not have the means to procure one. Following step by step an anterior hypothesis, I would then have assigned its true nature and found a place among the orders of natural history, for this creature whose sickly posture I admired the nobility of. With a satisfaction at not being completely ignorant of the secrets of his dual organism, and a hunger to know more, I considered him in his enduring transformation! Though he did not have a human face, I thought him beautiful like the long tentacular filaments of an insect, or rather, like a hasty burial, or indeed, like the law of the reconstitution of mutilated organs, and in particular, like an eminently putrescible liquid!

Paying no attention to what was going on around him, the stranger with the head of a pelican stared into the distance. Some day, I will tell the rest of this story. In the mean time, I will continue my narration with dismal haste, since if, on your part, you cannot wait to find out where my imagination is leading (please heaven that it was indeed nothing more than my imagination!), I, on my part, have resolved to finish telling this tale in one sitting (and not in two!). Meanwhile no one has the right to accuse me of lacking courage. But when faced with circumstances of this kind, one feels one’s heart throbbing against the palm of one’s hand.

In a small, almost unknown port in Brittany, an old sailor, rigger and calker, had just died. He was the hero of a terrible tale. He had been a captain and had sailed for a ship-owner in Saint-Malo. Following an absence of thirteen months, he returned home at the point when his wife, still bedridden, had just delivered him a son and heir, in recognition of whom he recognised no right. The captain betrayed neither his surprise nor his anger. Coldly he asked his wife to accompany him on a walk along the town’s battlements. It was January. The battlements of Saint-Malo are elevated and, when the wind blows from the north, even the most intrepid shiver and recoil. The poor wretch obeyed, calm and resigned. When she got back home, she was raving and delirious. She died that night. But she was only a woman. While I, a man, in the presence of a drama no less great, was not sure whether I would have enough control over myself for the muscles of my face to remain fixed and motionless!

As soon as the beetle had arrived at the foot of the mound, the man raised his arm towards the west (precisely in that direction a condor and an owl were engaged in aerial combat), wiped from his beak a long tear which presented a system of diamantine colouration, and said to the beetle:

― Wretched ball! Have you not rolled it long enough? Your thirst for revenge is still not satisfied. Already this woman, whose arms and legs you have bound with pearl necklaces, in such a way as to form an amorphous polyhedron, before dragging her, with your tarsals, on rocky roads and across valleys, through bramble and briar ― let me come closer and see if it is still her! ― has seen her bones compounded with injury, her limbs, polished by the mechanical law of rotational friction, become confounded in the unity of coagulation, and her body present, instead of the primordial lineaments and natural contours, the monotonous appearance of a homogenous whole that resembles only too much, by the confusion of its divers ground elements, the uniform mass of a sphere! She died long ago; lay he remains to rest, and take care not to increase, beyond irreparable proportions, the rage that consumes you: it is no longer justice; as egotism, hidden in the teguments of your brow, like a phantom, slowly lifts the veil that covers it.

The condor and the owl, carried along by the vicissitudes of their battle, had come closer to us. The beetle trembled at these unexpected words and what, on any other occasion, would have been an insignificant gesture, became, on this occasion, the distinctive mark of a fury that knew no bounds: he rubbed his posterior thighs against the edge of his forewings, making a loud piercing sound:

― Who are you, pusillanimous creature? It seems to me that you have forgotten certain strange developments of the past; you retain no memory of them, brother. This woman betrayed us both, one after the other. First you, and then me. Such an offense must not (must not!) fade from recollection so easily. So easily! Your magnanimous nature allows you to forgive. But do you know whether, in spite of the unusual arrangement of this woman’s atoms, reduced to a doughy mush ― it is no longer a question of ascertaining whether, on first inspection, anyone would believe this body to have been enlarged by a considerable amount of matter, rather by two powerful wheels thrown into gear than by the effects of my fiery passion! ― she still exists? Be quiet and let me avenge myself!

He continued his carousel, and drifted away, pushing the ball in front of him. When he was some distance away, the pelican cried:

― This woman, with her magical powers, has given me the head of a bird, and turned my brother into a beetle: perhaps she deserves even worse punishments that those I have just enumerated.

And I, unsure whether I was dreaming, and guessing from what I had heard, the nature of the hostile relations that united the owl and the condor in bloody combat, tossed my head back, like a hood, to give my lungs a greater ease and elasticity, and directing my eyes towards the sky, yelled:

― You there! Stop your fighting! You are both right. To both of you she had promised her love, and therefore, you were both deceived. But you are not the only ones. She deprived you of your human forms, making a cruel sport of your most solemn suffering. And you still do not know whether to believe me! She is dead, in any case, and the beetle inflicted a punishment whose imprint, despite the pity of the first betrayed, can never be effaced.

At these words, they gave up their quarrel, and stopped tearing feathers and strips of flesh from each other’s bodies: they were right to behave thus. The owl, beautiful like a memory on the curve described by a dog running after its master, plunged into the cracks of a ruined convent. The condor, beautiful like the law of the arrested development of the chest in adults whose propensity towards growth is not proportional to the number of molecules their body assimilates, disappeared into the highest layers of the atmosphere. The pelican, whose generous pardon made a great impression on me, because I thought it unnatural, stood on his mound with the majestical indifference of a pharaoh, as if to warn human navigators to pay heed to his example and to save the fate of their love from dark witches, and stared into the distance. The beetle, beautiful like the trembling hands of an alcoholic, disappeared at the horizon. Four more existences that could be could be struck from the book of life. I tore a whole muscle in my left arm, as I did not know what I was doing, so moved was I by the presence of this quadruple misfortune. And I, who thought it was excremental matter. What a fool am I!