by Alfred Jarry

translated by Samuel Lees

MURAL MORALS

If a thousand years from now a historian were to examine the public notices on alcoholism issued by the health department ― assuming that the paper is strong enough to last that long, and has only seldom been used for purposes other than those for which it was intended ― he would not find any difference between these documents and those left by the religious feuds of yore. The problem of whether or not to abjure alcohol is the modern form of the question of communion under both kinds. These questions obsessed mankind in times when such concerns, by a singular transposition, could determine one’s fortunes in a future life. It was important to know whether one’s chances of escaping certain tortures, described in meticulous detail, would be improved by consuming the bread of life on its own or with a glass of wine.

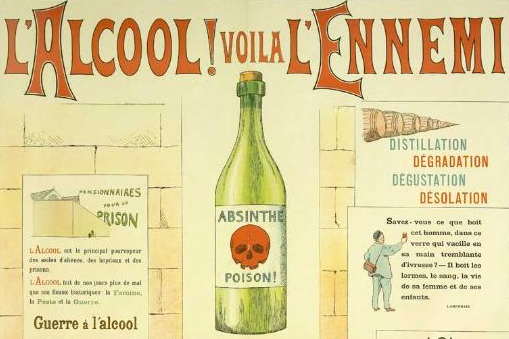

The fear of hell having largely diminished, some of those individuals who make it their business to meddle, by interest or naivety, in the affairs of others, took advantage of this great bonfire, as one might do with any blaze that has begun to dwindle, by bringing it nearer. They brought its flames into this life. Man is still threatened, if he does not obey certain prescriptions arbitrarily ordained, with inflammation of the bowels and calcination of the bones. There would not have been any point imagining new and unprecedented horrors when the existing ones had been tried and proven to work. The posters against absinthe depict a green figure resembling a medieval image of the devil. Doctors are the new priests who benefit, in the eyes of the mob, from the distinction ― for now at least, and perhaps for some time to come, as they love to be frightened ― of being the keepers of secrets and mysteries. The ignorant have a special word for those among them who boast a rare, nuanced form of ignorance: they call them experts.

These experts claim that the human being is always willing to deny himself the opportunity for immediate gratification in favour of an ulterior pleasure or in order to avoid a future pain. This idea has known little refinement since the days of primitive hedonism. The pleasure of the future does not promise to be any greater in size; its appeal comes from the fact it is far away. Notorious villains, who have made use of this mechanism, have revealed themselves expert philosophers. The notion of equilibrium, of justice, is as native to life as that of thrift. Thus even the ant will economise in order to ensure food security. This security consists in a series of privations. As for the equilibrium of pleasure and pain, there is no good reason to believe it exists; in any case, if there is such a thing as an equal number of joys and pains ― a strange idea ― it is not to be found in any one individual: there are those who are strong by nature and others to whom everything is a death threat.

… Meanwhile, in its dispensaries and furnaces, the health department slakes the thirst of its disciples with the image: not a single glass or jug is to be found on the tables of the refectory; the healthy and bracing walls are strewn with mouth-watering representations of human forms, their skin torn away to reveal brain and lungs, and violently illuminated, showing the ravages of alcoholism.

Mr. Rigaud, who presided over the mayors’ banquet at the World’s Fair on the 22nd of September 1900, a vigorous man in his nineties, owes his excellent health to having replaced two of his meals with small glasses of alcohol. How many centuries could he expect to live, a fortiori, were he to drink two large glasses?

The world’s heaviest drinker, doctor Mooney of Kentucky, a septuagenarian, has calculated that, since the age of twelve, he has consumed three hundred thousand francs of whiskey: this is the reason for his longevity and the first instance of the saying: Time is Money.

In Rome, the prize awarded for first place in the great chariot race at the foot of the Capitolium, above the gold crown given to ordinary generals, was nothing other than a glass of absinthe… Let us note, while we are on the subject, that in his enumeration of the more or less devastating “poisons” hidden in this liqueur, Mr. Laborde neglected to mention spurge, which contributes to its opaline hue and its incomparable digestive qualities.

On the 23rd of January 1903, Mr. Charles-Henri Desmarcheliers, a cobbler and alcoholic, in excellent health, had a wife who was sobre, infertile and sick…

That is why the former killed the latter.

Lastly, let us expose the hidden motives of the health department, who will not tire in their efforts, for the excellent reason that they are being bribed by a well-known manufacturer of absinthe, eager to furnish themselves with a reason to hike their prices.

Notes

The Exposition Universelle was a world’s fair held in Paris in 1900 to celebrate the achievements of the previous century. Among the attractions was a large banquet involving 20,777 mayors from France, Algeria and other colonies.